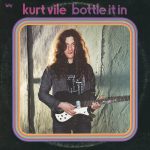

KURT VILE, Bottle It In (CD/LP)

Playing big theatres and releasing an average of an album a year for eight years suggests steely professionalism, but Philadelphia songwriter Kurt Vile still thankfully sounds like a guy on a skateboard who tries to sell you a 10-bag after asking you for directions. His distinctive drawl suggests a somewhat fugged mind, something that the lyrics back up: on Bassackwards, he’s doing a radio show under the influence of something or other, saying of his co-host “I appreciate him to the utmost degree” with a stoner’s ironic grandeur. On Hysteria, he “took a drink of a dream smoothie / and all of a sudden I’m feeling very loopy”. But if he’s high, he’s surfing a crystalline state of amused, outward-facing insight, rather than crashing into catatonic self-regard (even if, on Mutinies, he bashfully admits to popping pills to shut up the voices in his head). There’s a sturdy quality to the neat, cute repetitions in his guitar backings, the bamboo that the bindweed of his voice trails around, and while the drums still tread the same happy trudge, he adds some well-chosen new flavours. There’s mellifluous crooning on Rollin With the Flow, country-soul backing vocals from Warpaint drummer Stella Mozgawa on the beautiful One Trick Ponies, a rather menacing electronic murk behind Check Baby, a bit of deep clarinet on the title track; Cold Was the Wind puts the bong in bongos. Best of all is his decision to let four songs wander up to, and sometimes over, the 10-minute mark – this amplifies the bean-baggy vibe, and lets Vile’s idling poetry really find its slacker voice. It also allows room, on Skinny Mini, for two great guitar solos, where jazzy improvisation turns into big fuzz chords, like a traditional solo deconstructed into separate notes. Lesser musicians would make these songs as boring as a drugs story you aren’t involved in, but Vile ultimately has such an instinctive facility for melodic logic that behind the shaggy locks and purple haze, there’s a clear-headed, big-hearted songwriter at work.

THE BOTTLE ROCKETS, Bit Logic (CD/LP)

As the world is running down, the Bottle Rockets offer a no-nonsense view of their surroundings through Brian Henneman’s sharp songwriting and some rocking country guitar playing by John Horton. “Bit Logic” is the Missouri band’s 13th album since their 1993 self-titled debut — which had backing vocals from Jeff Tweedy and Jay Farrar — released when the Bottle Rockets were in the midst of the alt-country/Americana explosion. To say little has changed since then would be an exaggeration because their lineup is different — with the current one intact for well over a decade — and might create an impression of stagnation. Au contraire. Henneman’s keen eye for the complications in simple lives only gets sharper and Horton’s guitar is ever more thrilling as is the rhythm section of founding member Mark Oatmann (drums) and “new kid” Keith Voegele, on bass since 2005. “Bad Time to Be an Outlaw” has funky guitars parts coming at you from both speakers, like a roots-rock “Marquee Moon.” It adds itself to the long list of songs lamenting the glitz and marketing ploys of the Nashville scene. “My music’s good but my income sucks,” Henneman sings, a realistic grievance. “Carrie Underwood don’t make country sound/But she can afford it when shit breaks down,” he intones later in the song. “Human Perfection” finds beauty in immediate surroundings, while “Knotty Pine” is a tribute to a songwriting room (”a psychiatrist-treehouse composite”). “Highway 70 Blues” paints the frustration of an Interstate traffic jam and “Lo-Fi” remarks how technological advances sometimes diminish the fidelity of music listening. “Silver Ring” ends the album on a tender note, as Henneman, whose voice combines Dave Edmunds, Levon Helm and John Prine, bears witness to a most crucial relationship, the one with your true love. You’ll have to find your own solutions, but on “Bit Logic” the Bottle Rockets offer some clues.

ELVIS COSTELLO & THE IMPOSTERS, Look Now (CD/LP)

“History repeats the old conceits,” Elvis Costello sang thirty-six years ago on Imperial Bedroom, his finest hour of versatile pop mastery. But even back then, he was rarely interested in repeating himself – going from the angry, young almost-punk of 1978’s This Year’s Model to the literate, political New Wave of 1979’s Armed Forces to his “soul record” Get Happy! to the barbed pop of Trust and the country tribute Almost Blue. Or, more recently, following up 2010’s National Ransom (rock and country about the Great Recession), with 2013’s Wise Up Ghost, a successful album of trenchant funk with the Roots. Yet, even if he’s never really returned to a signature sound, he’s also never shied away from the golden-age LPs that made his legacy, packing his live sets with killer versions of Seventies and early Eighties favorites backed by the Imposters, a band that includes keyboardist Steve Nieve and drummer Pete Thomas, who’ve been playing with him throughout his entire career. Costello’s his first new album in five years finds him squaring his restless artistic impulses with his storied past. He says it’s an attempt to connect Imperial Bedroom, where he essentially combined McCartney-esque compositional brilliance with Lennon-esque lyrical bite, and 1998’s Painted from Memory, on which he collaborated with iconic pop songwriter Burt Bacharach. Costello was in his late twenties when Imperial Bedroom was released, and the songs showed it, focusing on people making their first fumbling negotiations toward and struggles within long-term relationships. The biggest song off his previous LP, 1981’s Trust, had been “Clubland,” a searing take on going out. Imperial Bedroom had highpoints like “The Long Honeymoon” on which he sang “there’s no money back guarantee on future happiness,” the grinding sound of youngish people moving into oldish realities. That dead-end sense haunts the people he sings about on much of Look Now; they’re further down the road of life yet just as troubled because, as always, a satisfied person in an Elvis Costello feels like someone who got off at the wrong bus stop. “It was something I just couldn’t understand until I slipped my finger into the band,” observes the narrator on “Mr. and Mrs. Hush,” a punchy soul-kissed tune in which a man pleas for the simple pleasure of understanding his lover’s desires. ” I don’t know if I’m deep down right inside her heart or outside her door.” The album opener “Under Lime,” decks out an elegant melody with Sgt. Peppers-like horn flourishes, while Costello spins a short story about an aging singer and his creepy yet emotionally multi-faceted encounter with a young woman who works as a production assistant on a TV show he’s been booked to perform on: “Whatever you think, don’t let him drink,” she is warned. It’s classic Costello, breathlessly jammed with images and wordplay but still effortlessly tuneful, and also timely, tinged with post #metoo resonance. The standout “Burnt Sugar Is so Bitter,” which Costello co-wrote with Carole king, is about a woman coming to terms with life after her husband has left her, packing a novel into three minutes that brings to mind Steely Dan’s Countdown to Ecstasy. Bacharach arranges and plays piano on two songs, “Don’t Look Now” and “Photographs Can Lie,” stately, somber ballads about aging and loss. What sets these songs apart from many of the other Costello LPs that have come out since the Nineties is that they don’t seem like mere genre experiments – moments like “Unwanted Number” and “Dishonor the Stars” are seasoned, if also somewhat studied, takes on the kind of wry, well-observed pop classicism that’s been the hallmark of his genius. There are moments here where you wish the melodies were more indelible and times where the classiness of the musicality gets in the way of the urgency of the songwriting. But on the whole he’s hit his mark, updating the emotional and musical possibilities behind some of the most beloved music of his great career.

JOHN HIATT, The Eclipse Sessions (CD/LP)

This is John Hiatt’s first album in four years and 23rd overall, enlisting producer and stellar keyboardist Kevin McKendree who has done excellent work for Delbert McClinton and Tinsley Ellis to name just a couple. This marks a departure from Hiatt’s association with Doug Lancio as guitarist and/or producer for his previous three albums. For The Eclipse Sessions Hiatt fronts either a trio or a quarter depending on whether McKendree ‘s 17-year-old son, guitar virtuoso Yates McKendree, is present with Hiatt’s long-time drummer Kenneth Blevins as well as bassist Patrick O’Hearn. When Yates does play, he impresses with his sharp soloing and knack for just the right fill whether electric or acoustic slide. Check the latter on the “The Odds of Loving You.” On top of that, Yates engineered the album. Now 66, Hiatt took time off to contemplate his next step and spend more time with his family (which includes emerging artist Lilly Hiatt). It’s not clear what inspired him to get back into the studio for this raw, stripped-down, blues at the core session but it doesn’t matter. He feels that this is one of three best albums he’s made. He cites 1987’s Bring the Family, done with an all-star combo led by Ry Cooder, and 2000’s largely solo acoustic Crossing Muddy Waters that earned a Grammy nomination as the other two in this trilogy. He says, “The three albums are very connected in my mind. They all have a vibe to them that was unexpected. I didn’t know where I was going when I started out on any of them. And each one wound up being a pleasant surprise.” The title takes its name from the solar eclipse of August 21, 2017, when three of the songs were recorded. He characterizes the momentary darkness in Nashville that day as rather magical and symbolic of a kind of harmonic convergence. That togetherness comes through in these loosely structured, raw, unadorned songs where the weathered quality of Hiatt’s voice seems to carry even more emotion than we’ve heard from him. And yes, there are the obvious nods to aging and mortality as gleaned in titles like “Over the Hill” and “Outrunning My Soul” or, for example this passage from “Hide Your Tears”- “I don’t spend too many days/Thinking about the reckless ways/A man tries to outrun his death/Or a broken heart runs out of breath.” In fact, during his hiatus, Hiatt composed the last track “Robber’s Highway” that in its own inexplicable way may have served as the inspiration to record again. He was thinking that even though it was once easy to write songs, maybe the spark was gone (“I had words, chords, and strings/now I don’t have any of these things”) only to find his muse again with this set of gems. The album begins with the relatively carefree “Cry to Me,’ followed by the classic melodic Hiatt sound in “All the Way to the River” before becoming very stark by the fifth track, “Nothing in My Heart.” Preceding that tune is the lost love lamentation “Aces Up Your Sleeve” and the rugged, rocking “Poor Imitation of God.” We are in a different time now than when Hiatt had those classic songs like “Looks Like Rain,” Memphis in the Meantime” and “Slow Turning” among several others. As good as some of these songs are, they may never reach that kind of lofty status. Just the same, Hiatt still has that knack of killer lines. “Over the Hill’ has “I’m long in the tooth/What can I say/I take huge bites out of life” “Robber’s Highway’ has “Can’t feel the fingers of one hand/last night felt like a three-night stand.” Listen to Hiatt’s road-weary voice, his sturdy guitar, and the stripped-down accompaniment; it seems he’s got plenty left. This is as expressive as he’s ever sounded.

BUTCHER BROWN, Camden Sessions (CD/LP)

Coming close on the heels of their earnest tribute to Afrobeat great Fela Kuti, Virginia’s funk-jazz masters Butcher Brown goes back to doing its usual analog, bell bottoms thing with Camden Session. At least, if the advance title track is any indication of the rest of the album. “Camden Session” is a slow-going, bud-burning quiet storm led by Marcus Tenney’s sax that picks up the pace only a little in the chorus. Listen behind him you’ll find DJ Harrison’s electric piano, Andrew Randazzo’s bass, Morgan Burrs’ guitar and Corey Fonville’s drums entwine to make a mushy groove, and Burrs steps out front for a lengthy but chops-filled jazz guitar showcase. Echoes of Grover Washington, the Headhunters and Roy Ayers can be heard without outright aping them; Butcher Brown distills their influences into a classic sound all their own.

YOUNG THE GIANT, Mirror Master (CD

TOM MORELLO, Atlas Underground (CD/LP)

COLTER WALL, Songs Of The Plains (CD/LP)

GENE’S CLASSICAL/BLUES CORNER:

BOB MARGOLIN, Bob Margolin (CD)

BOB MARGOLIN, Bob Margolin (CD)

Bob played and sang every note, produced, recorded and mixed this album. Six new original songs are his blues for today’s world. He also interprets nine songs he learned “back in the day” from his legendary friends Muddy Waters, The Band, Johnny Winter, Jimmy Rogers, Snooky Pryor, Pinetop Perkins and James Cotton. Gene says: Any Bob Margolin new utterance is of interest and value to blues followers. His playing and down home integrity has been a Horizon favorite flavor since the old days when we first saw him and bought those wonderful records when he was guitarist in the legendary smokin’ 70’s era Muddy Waters Band (check the Muddy performance on The Last Waltz!). yessir.

KIM KASHKASHIAN, J.S. Bach Six Suites For Viola Solo (CD)

KIM KASHKASHIAN, J.S. Bach Six Suites For Viola Solo (CD)

The poetry and radiance of Bach’s cello suites (BWV 1007-1012) are transfigured in these remarkable interpretations by Kim Kashkashian on viola, offering “a different kind of sombreness, a different kind of dazzlement” as annotator Paul Griffiths observes. One of the most compelling performers of classical and new music, Kashkashian has been hailed by The San Francisco Chronicle as “an artist who combines a probing, restless musical intellect with enormous beauty of tone.” An ECM artist since her legendary recording of the Hindemith sonatas in 1985, she brings to Bach the commitment and intensity revealed in her widely acclaimed (and Grammy-winning) account of Kurtág and Ligeti. Gene says: The amazing and unstoppable virtuosity of Kim Kashkashians viola work and her sprawling catalogue now visits the iconic Bach Cello suites played here all six across 2 full CDS. What a treat, what intense, gossamer and sombre beauty when a forward looking artist of her stature and experience offers these 18th century touchstones played as if newly written for us. Repeated playings only deepen the appreciation anew for her performance of these very familiar Bach jewels.

COMING SOON:

CLOUD NOTHINGS, Last Building Burning (10/19)

GRETA VAN FLEET, Anthem Of The Peaceful Army (10/19)

JASON ISBELL & THE 400 Unit, Live At The Ryman (10/19)

MINUS THE BEAR, Fair Enough (10/19)

WILL OLDHAM, Songs Of Love & Horror (10/19)

And don’t forget these STILL-NEW platters that matter!

THE MARCUS KING BAND, Carolina Confessions (CD/LP)

Carolina Confessions is where the wunderkind child prodigy of blues guitar grows up. The album features 10 brand-new songs, all written by Marcus except for ‘How Long,’ which was co-written with the Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach and veteran songwriter Pat McLaughlin. Whether it’s the searing rock exorcism of ‘Confessions’ or the propulsive road-bound soul of ‘Where I’m Headed,’ Marcus exhibits an almost Southern gothic sensibility in his songs, owning up to failed relationships, portraying his complex connection with his hometown, arraying a sprawling musical firmament in the process. Marcus and his five bandmates – drummer Jack Ryan, bass player Stephen Campbell, trumpeter/trombonist Justin Johnson, sax player Dean Mitchell and keyboard player DeShawn ‘D’Vibes’ Alexander – are in top form on Carolina Confessions, exhibiting an intuitive sense of control and expression as they tackle their most sonically layered and emotionally complex compositions to date. Marcus and Co. have seen the world over the last few years, becoming one of the hottest new bands in the country in the process. Carolina Confessions is where King takes stock, retrenches and lets his gruff soulful voice and fiery guitar playing lead his boys back into the fray.

PHOSPHORESCENT, C’est La Vie (CD/LP)

“I was drunk for a decade,” sings Matthew Houck on These Rocks, a lilting country lullaby about laying down self-imposed burdens. For a decade and a half now, Houck has been recording as Phosphorescent, running the gamut of Americana’s ever-broadening expanse, from eccentric alt-folk to upbeat stompers (even to a Willie Nelson tribute album). His last record, 2013’s Muchacho, was a high born of hard living and hard touring: during its making, he told Pitchfork, he’d “lost the place, lost the girl, and lost my mind”. Five years on, he’s built himself a new studio in Nashville, found new love and had two children. Though life has its shadows still (the motorik psych-country epic Round the Horn, the vocoder lament Christmas Down Under), the core of C’est La Vie is radiant happiness, Houck’s familiar sounds buffed to a transcendent shine: New Birth in New England is snappy and jubilant with an irresistible hook, My Beautiful Boy melting with liquid pedal steel and pure delight. On the title track, with its contentedly chugging organ, Houck happily forswears extremes: “I don’t write all night burning holes up to heaven no more.” And yet, it seems, he’s closer to bliss than ever.

NATHAN BOWLES, Plainly Mistaken (CD/LP)

Banjoist and percussionist Nathan Bowles’ latest album is at once old and new. He takes some of the oldest instruments known to humanity and wields them in ways that both evoke the past and challenge their future roles in pop and roots music. Plainly Mistaken is the Durham, North Carolina-based Bowles’ fourth solo album, but only his first recorded with a full band. Members of Mount Moriah, Jake Xerxes Fussell’s band, and CAVE all contribute to the record, which is fitting considering Bowles previously spent years performing and touring with Fussell, as well as contemporaries like Steve Gunn, The Black Twig Pickers, and more. Over the course of nine tracks, Bowles showcases his technical mastery of the banjo, as well as his ability to remove it from hillbilly stereotypes. Only two songs on Plainly Mistaken have vocals. The first, “Now If You Remember,” is Bowles’ version of a song from English singer Julie Tippetts’s 1976 album Sunset Glow — one written by seven-year-old Jessica Constable that begins his record with an eerie role reversal. About halfway through the record, Bowles offers a cover of a classic bluegrass song, “Ruby,” which was made famous by The Osborne Brothers and Buck Owens, and even interpreted by The Silver Apples. Bowles enmeshes his tense and trippy version with his own improvisation, though, calling it “Ruby/In Kind I” on the LP. Still Bowles’ best work really stands out with his originals. Some, like “Elk River Blues,” “Fresh Fairly So,” and the lovely closing “Stump Sprout” sound as familiar as the aforementioned old banjo tunes thanks to their clawhammer strumming and traditional chord progressions. But it’s the more experimental and progressive songs like “The Road Reversed” and “Girih Tiles” (the latter performed on a custom banjo/bazouki hybrid instrument called a “mellowtone”) that really show the extent of Bowles’ creativity. The banjo already is a droning instrument, especially in standard G tuning where the high G string easily makes an open chord. But on “The Road Reversed,” Bowles incorporates a droning double bass what sounds like a droning harmonium —interjected by brief trebly woodwind chirps — to create a 10-and-a-half-minute journey that’s simultaneously pastoral and cosmic. It’s that kind of wild musical exploration — one that makes an already iconic sounding instrument seem like another — that makes Bowles’ banjo playing such an important addition to the canon of bluegrass and roots music.

CAT POWER, Wanderer (CD/LP)

Chan Marshall’s career is solitary and self-sustaining like few others. Her catalog is a mountain range, each peak indifferent to what preceded it and unconcerned with what follows it. With barely more than her voice and a guitar, she has built a rich and variable universe spanning an array of moods—unnerving, consoling, paranoiac, sensual—and her albums situate themselves along those moods like stations of the cross. They don’t change much from one to the next, but even if they sound similar, they each feel different. Wanderer is her 10th album, her first in six years, and the first that revisits each and every one of those moods, at least fleetingly. The opening title track brings her wondrous voice to the fore, highlighting the chocolate rasp she used so well on 2006’s The Greatest. “Robbin Hood” is based on the same minor chord as “Werewolf” from 2002’s You Are Free. These are paths Marshall has led us down before—the piano chords pooling into their own delay pedals, fingerpicked guitars lingering on a minor chord like a blank stare held a beat too long. Rob Schnapf, who’s also produced for Elliott Smith and Beck, shapes the record with an ear for low, bass sounds, both the throatier, huskier notes in Marshall’s voice and the rounded pop of the hand-slapped percussion on “In Your Face.” The resulting mood lands somewhere between swaying hips and nervous rocking. The blissed-out piano of “Horizon” feels both beautiful and slightly vacant, like it could be streaming down from heaven or piping weakly into a drugstore. It is one of the album’s most arresting songs, in part for the brittle, anxious energy rattling around inside Marshall’s lyrics, as they often do, arrow themselves towards an unnamed “you,” carrying notes of resentment and affirmation. On Wanderer, she often blends the two, warning, indicting, and soothing all in the same breath. The Rihanna cover “Stay” reminds us how Marshall can rearrange a song simply by squinting at it—suddenly the most important line was buried somewhere in the middle. The lyrics on “Stay” are pared back but otherwise recognizable, as is the arrangement, but the pauses happen in all different places, making Marshall’s “I want you to stay” a completely different sentence from Rihanna’s. Another time-stopper is the Lana Del Rey collaboration “Woman.” Their voices—deep, confident, hooded—blend into one, with Del Rey technically on backup. Del Rey’s universe, full of bright candy reds and pastels, does not resemble Marshall’s on the surface, but the two of them share a weary resignation, a survivor’s determination, that makes their duet feel like two halves of one circling thought. The chorus is simply “I’m a woman,” but repeated with varying shades of defiance, pain, pride, warmth, and urgency. The word “woman”—as label, as cultural identity, as epithet—streaks its way up into the sky, glittering and burning off the fog.