STURGILL SIMPSON, Sound & Fury (CD/red vinyl LP)

Ever since Sturgill Simpson was anointed the second coming of Seventies country with his 2014 release, Metamodern Sounds in Country Music, the 41-year-old Kentucky Navy vet has spent the past half-decade making a show of his discomfort with any such label. Simpson followed up that career-making record with 2016’s A Sailor’s Guide to Earth, an idiosyncratic Elvis/soul-hybrid song cycle about his son, opened for Guns N’ Roses, livestreamed a performance of himself busking outside the CMA awards, and most recently, convinced his label to help finance a million-plus dollar anime film. That litany of iconoclastic gestures have, of course, only ended up bolstering the very image of old-school Nashville dissident that Simpson says he’s been trying so hard to walk away from in the first place. Enter Sound & Fury, which is simultaneously the most left-field, decisively non-country offering of Simpson’s career and precisely the record anyone who has been paying any attention to his career over the last several years would have expected him to make. Over ten songs, Simpson leads his tight-knit rock quartet through a super-charged flow of indignant Southern Rock (“Fastest Horse in Town”), strutting disco-boogie (“Sing Along”), and pulsing modern blues (“Best Clockmaker on Mars”) that do away with the typical melodic, structural conventions of country and folk. “A sleazy synth-rock dance record,” he’s called it. Sound and Fury begins much in the same way as Simpson’s recent live set: with an exploratory psych-blues jam. Establishing the tone on the four minute instrumental “Ronin,” Simpson is smart enough to cede much of the narrative storytelling of Sound & Fury to his guitar. As a guitarist, Simpson is uninterested in conventional guitar god shredding; his playing is curious, fluid and full of wonder. The most thrilling moment on the record, and perhaps in Simpson’s entire catalog, comes nearly two minutes into “Make Art Not Friends,” the album’s shimmering creative introvert anthem centerpiece, when Bobby Emmett’s hypnotic keyboard pattern gives way to a booming staccato guitar riff. “Think it’s time to change up the sound,” as Simpson puts it. When Simpson does sing, much of what he has to say is similarly self-referential. He’s angstier than ever on Sound and Fury, plagued by his public platform, preoccupied with the way he’s been misunderstood and boxed in by an unforgiving music industry. Simpson sells such discontent with a fury that makes it seem as though he’s the first rockstar who’s ever had to deal with such problems. He’s “spent the last year burned out of [his] mind.” He’s “been pulled a million ways all at the same time/it’s enough to make anyone go insane.” Success and recognition, so it seems, have not been kind to the singer-songwriter. “Living the dream,” he sings, in an unsubtle reference to the Metamodern fan favorite of the same name on “Mercury in Retrograde,” “makes a man want to scream/Light a match and burn it all down.” On A Sailor’s Guide to Earth, Simpson was relearning to see the harsh world around him through the eyes of his young son. “Bullshit on my TV/Bullshit on my radio,” he sang on the righteous Stax-rave “Call to Arms,” “Hollywood’s telling me how to be me/The bullshit’s got to go.” Three years later, Simpson sounds both defiant and defeated, but mostly just fed up with the world of surface-level fame in which he now finds himself. “Bullshit sells,” he sing-shouts, surrounded by his wall of Telecasters, “don’t you ever forget.”

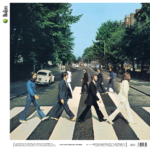

THE BEATLES, Abbey Road (50th Anniversary Edition) (LP/3xLP w/ book/3xCD w/ Blu ray)

Even by Beatles standards, Abbey Road has always been an album full of mysteries. How could the world’s most beloved band make their sunniest, warmest, most charming music while they were in the middle of breaking up? How did John, Paul, George and Ringo come together to drop their all-time biggest crowd-pleaser, while gearing up to go their separate ways? The eternal mysteries of Abbey Road only get deeper as you explore the revelatory new Super Deluxe Edition, released on the album’s 50th anniversary. It follows the recent Sgt. Pepper and White Album boxes — and like them, it will transform the way fans hear and argue about this Abbey Road has always represented a historic peak of pop invention and perfection — that’s why Drake just got the cover tattooed on his arm. To this day, it remains their biggest seller. But it’s also their bittersweet goodbye. After the disastrous Get Back sessions in early 1969, they regrouped for one last blaze of glory. The final moment when all four were playing together was when they cut “I Want You (She’s So Heavy).” All four knew it was the end. For the last time in their lives, they were writing, playing and singing Beatles songs. For any other band, this situation might have tempted them into hoarding the best songs for their solo records. But the Beatles were far too competitive, too ambitious, too vain, too bloody-minded for that. They didn’t merely bring in brilliant songs—they brought brilliant Beatle songs, as if they knew they’d never get another chance to write tunes for these voices to sing. John never wrote another “Because,” just like George never wrote another “Something” or “Here Comes The Sun.” These were their love songs to being Beatles together. Giles Martin and Sam Okell have done a new mix in stereo, 5.1 surround sound and Dolby Atmos. The mix does wonders for moments like the three-way guitar duel in “The End,” with Paul, George and John trading off solos live on the studio floor. The Sgt. Pepper and White Album sets were packed with mind-blowing experiments and jams, but Abbey Road is considerably more focused. In these 23 outtakes and demos, you hear a band in the zone, knowing exactly what they want to do, working hard to finesse the details, even the ones only they’ll notice. They’re playful, like when John messes with the lyrics of “Mean Mr. Mustard”: “His sister Bernice works in the furnace!” But it’s four confident men, determined to show off for the world — and more importantly, for each other. There’s a fantastic alternate version of “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” from Trident Studios in London, where the lads get interrupted by angry complaints about noise from the neighbors. John politely agrees to turn down the volume, after one last take. Then he tells the band, “Last chance to be loud!” There’s also a poignant outtake of “The Ballad of John and Yoko” — just John on guitar and Paul on drums, while the other two are out of town. John quips, “A bit faster, Ringo.” Paul replies, “Okay, George!” It’s a touching joke to overhear. They’re still in love with this band of theirs. Abbey Road has a warmth unlike any of their other music, which is why its popularity never dips. These tunes fired up that restless hunger the lads had to impress each other, which none of them ever really lost, even after the band split.

JOHN COLTRANE, Blue World (CD)/LP)

Three weeks after Miles Davis’s exhumed and embalmed 1985 Rubberband release comes a previously unknown John Coltrane 1960s-quartet session called Blue World – short tracks and alternate takes on early Coltrane originals, recorded for a Canadian movie soundtrack in summer 1964, and never intended for release. But unlike Rubberband, Blue World – even if its movie agenda required simpler, and more lyrically explicit delivery than anything else this enthralling band was doing on the road or on record in 1964 – is still Coltrane quartet music to its vibrant core. Commissioned by Canadian director and Coltrane fan Gilles Groulx for a Montreal love story called Le Chat Dans Le Sac, Blue World features two takes of the exquisite 1959 ballad “Naima,” three of the catchily hooky “Village Blues,” the Sonny Rollins dedication Like Sonny, a harmonically audacious exploration of the modally stripped-down title track, and a storming ensemble performance on the standout, the mostly-improvised “Traneing In.” For newcomers to a 20th-century musical giant who transcended genre frontiers, it makes a very attractive sampler. For fans who know that the dark, lamenting Crescent preceded it, and the legendary and hippy-hypnotising A Love Supreme followed, it’s a fascinating hybrid of Coltrane’s song-based earlier methods, and his incandescently devotional late period.

BILLY STRINGS, Home (CD/LP)

In his short professional life, Billy Strings has proven he is aptly named, becoming a must-see live act by twisting upbeat bluegrass and acoustic Americana into expansive excursions. Now comes his second full-length studio record (following 2017’s debut Turmoil and Tinfoil) titled Home and while there are a few excessive passages, Strings rings true. The mix of acoustical bluegrass and electric experimentation starts right from the drop as the opener and first single “Taking Water” expertly gets freaky with digital effects, announcing to the listener that Strings and company are willing to go that extra mile. “Highway Hypnosis” travels that same route with sound effects and haunting voices, putting a unique twist on the standard road song while instrumental “Guitar Peace” plays with echoes and digital bleeps. More classic bluegrass-inspired tunes like the story-based “Must Be Seven” and the up-tempo, hypnotic “Long Forgotten Dream” are just two examples of Strings lyrical expression and damn hot picking. Strings is clearly more at home on the fast numbers (the blazing “Hollow Heart” is one example) and while ballads like “Running” and “Love Like Me” are well written, his voice needs to grow into them a bit more. Like many in these genres, Strings’ compositions can go on a bit long, however, when everything clicks, like on the almost eight-minute “Away From The Mire”, listeners will wish even more was offered. The title track and album centerpiece prove Strings is in a sweet spot, but he is not afraid to let his activist sideshow as “Watch It Fall” addresses climate change directly calling for action around a “Shady Grove” inspired sound. The albums second side successfully displays shorter numbers like the folksy Rick Danko sounding “Enough To Leave”, harmony-laden gospel sing-a-long “Freedom” and acoustic hoedown burner “Everything’s The Same”, all proving Strings doesn’t need to jam on and on to be effective and affecting. Unlike the more electrical jam offerings, bluegrass music works better on studio recordings as the instrumental crispness, storytelling tall tales and harmonies anchor the song, allowing the artists to still get loose. Billy Strings talents are clear as Home joins Greensky Bluegrass’s All For Money as the strongest releases in this genre for 2019.

THE NEW PORNOGRAPHERS, In The Morse Code Of Brake Lights (CD/LP)

Metaphorically and otherwise, things are falling down everywhere on the New Pornographers eighth LP: statues (“Colossus of Rhodes”), lovers (“Falling Down The Stairs of Your Smile”), performance conventions (“the 4th wall is falling on us” chime the worried singers on “Need Some Giants”), and especially people’s spirits — like the dude “in the parking lot of a dead mall” who closes out the album, as a pair of empathetic but shrugging guardian angels harmonize on the phrase “fallin’ into harm” (“Leather On The Seat”). Mainly, though, In the Morse Code of Brake Lights is the sound of empire falling, in not-so-slow motion, a palpable sense of plummeting that the Pornos, like the late great Tom Petty, channel through deliciously hooky music. As they make pretty explicit in “The Surprise Knock,” with its faintly dystopian Beach Boys vocal volleys, this is their usual MO of whistling in the coal mine: “Let it play in the background, tune out the sound,” they insist; “We’ll ride the chords as they repeat for years/ We may be on to something here.”There are plenty of automobile metaphors here, too, starting with the soaring opener “Backseat Driver,” which conjures being stuck in a car behind a petulant “child king,” and faintly echoes the New Porno signature “The Bleeding Heart Show,” a different sort of trapped narrative. The falsetto-spiked “Higher Beams,” with its traffic-jam tempo, string quartet, and buoyant “fuck you” reprise, suggests an inverse of the usual American immigration narrative: “Deep in the culture of fear, we all hate living here/ But you know when you can’t afford to leave?” As on the 2017 Whiteout Conditions, singer-songwriter Dan Bejar (Destroyer) is still MIA, which is a bummer — in Fleetwood Mac-ian terms, he’s the group’s DNA crossing of Stevie Nicks and Peter Green — but the upside is a unified album, more band than revue. Carl Newman remains default frontman/leader, writing nearly everything here (“Need Some Giants” is a co-write with Bejar). But Neko Case still brands every song she sings — just over half of ‘em — while Kathryn Calder, new-ish drummer Joe Seiders, and brand-new multitasker Simi Stone fill out vocal arrangements that remain as much the main attraction as any other element. Sure, the hooks and the lyrics are as sharp as ever, too, the latter functioning as part anxious messages-in-bottles, part baroque bubblegum life preservers. It’s panic-attack pop, fretting its way through vintage good-time chord changes, and letting us know we’re not alone.

THE REPLACEMENTS, Dead Man’s Pop (1 LP + 3 CD’s)

The Replacements story is filled with what-ifs and near misses. Their legend, essentially, is that if the chips had fallen differently, they might have become a popular band and had success into the 1990s, like their friends and rivals R.E.M.What if they had played ball with their label? What if they hadn’t made so many enemies? What if they hadn’t been so fucked up? In 1989, the question of the hour had to do with the band’s sixth album, Don’t Tell a Soul, and it goes something like this: What if they hadn’t released a record full of slick, radio-friendly pop-rock? With proper production, could this have been another classic? The question is asked because Don’t Tell a Soul was, for many years, the most maligned Replacements album, even if its reputation has improved some since then. Dead Man’s Pop attempts to answer these questions. The heart of Dead Man’s Pop is a new mix and sequence of Don’t Tell a Soul inspired by producer Matt Wallace just before he exited the project. Wallace wanted to mix the record himself, but could see the writing on the wall and knew the label wanted someone with a better ear for radio for the job (Chris Lord-Alge ultimately gave the record its modern-rock sheen). In this case, the final mix became the record’s fatal flaw, and Westerberg himself even bad-mouthed it. The quickie mix Wallace knocked out, once discovered, serves as the anchor for this set, which was named after the working title for the album. Many differences are subtle—it’s not like they turn Don’t Tell a Soul into Stink—and these are still the same songs and the same performances rendered with a simpler and more intimate tone. The opening “Talent Show” is perhaps the greatest improvement—Westerberg’s vocal is naked, the drums are reserved, and it comes over more like a studio jam than something assembled from individual parts. The guitars on “I’ll Be You” are more twangy and less cheesy, to use a common pejorative from the time of the album’s release. “Asking Me Lies” is newly airy and light, with the backing vocals more prominent. The common thread is that the guitars are cleaner, the vocals are clearer, and previously buried fills come to the surface, like the banjo in “Talent Show.” The set also re-sequences the album according to the Wallace tape. It’s more front-loaded now: No waiting until the second side to hear “I’ll Be You” and “Darlin One” (they are in slots No. 2 and 5, respectively). And ending the set with “Rock and Roll Ghost” after opening with “Talent Show” gives it a nice thematic frame, an innocent band taking a stab at one end and a fading relic thinking about the past at the other. For anyone skeptical of Don’t Tell a Soul, the most convincing argument for their vitality is the live shows from this period is Discs 2 & 3, which document a concert from June 1989 in Milwaukee.They played faster and crunchier than on record but the hooks were intact and, unlike a few years earlier, Westerberg remembered most of the words. And the setlist is stunning—the number of anthems they had on tap at this moment is almost unbelievable, drawing from 1984’s Let It Be through their then-new record and throwing in a few covers, including their terrific version of the Only Ones’ “Another Girl, Another Planet.” Don’t Tell a Soul wasn’t the breakthrough anyone hoped for, but it turned out to be their best-selling album, which might explain why many bands later accused of ripping off the Replacements (the Goo Goo Dolls, Ryan Adams) sounded the most like this era, when acoustic guitars and hushed vocals were prominent in the mix. At a certain age, you want nothing more than to feel special, and in Westerberg’s best songs on Don’t Tell a Soul, he offers hope that someone out there just might see the specialness in you.

THE GRATEFUL DEAD, Saint Of Circumstance: Giants Stadium, East Rutherford, NJ, 6/17/91 (5xLP/3xCD)