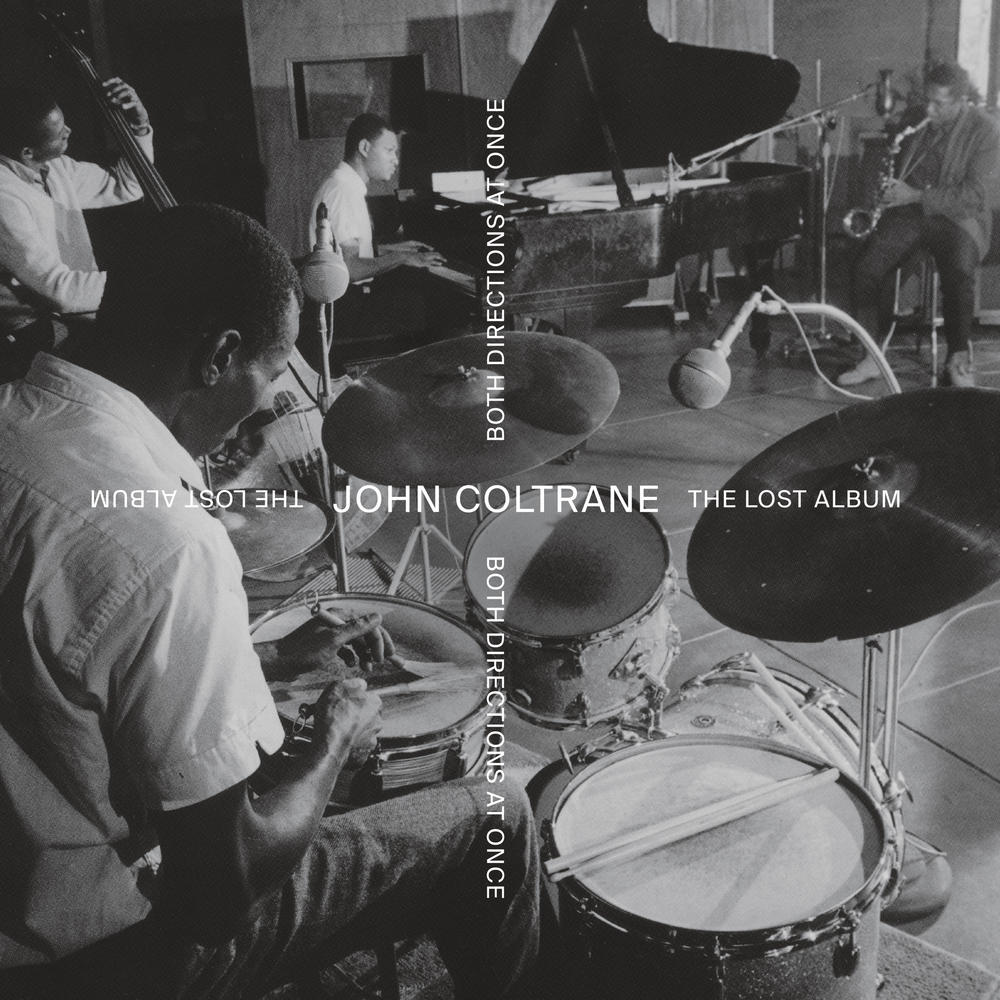

JOHN COLTRANE, Both Directions At Once (CD/LP)

The spinechillingly emotional saxophonist Albert Ayler said of his 1960s contemporaries John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders: “Trane was the father. Pharoah was the son. I was the holy ghost.” That sax triumvirate have many heirs (notably Kamasi Washington), but the spiritually restless Coltrane will always be the master. When the story broke of an unreleased Coltrane studio session, lost since its creation on 6 March 1963 but recovered from his late first wife’s archives, it was big news. That tape, featuring regulars McCoy Tyner on piano, Jimmy Garrison on bass, and Elvin Jones on drums, is now released as a single seven-track CD or LP, or a deluxe version with all 14 completed pieces. The Lost Album eavesdrops on a day in the short life of one of modern music’s giants in a period of turmoil. Coltrane is audibly striving to release himself from the shackles of traditional song structures here, despite still being drawn to their improv challenges, and simultaneously pursuing a more open, free-floating sound beyond song shapes and chords. Several takes of the same tunes make a strong case for getting the deluxe version to get a sense of just how unquenchably resourceful an improviser he was. The soprano solo on the Latin/swing theme Untitled Original 11386 launches fragmentedly in one version, venomously in another. The lyrical, ingeniously modulated balladeering on two takes of Vilia, from The Merry Widow, looks back to an earlier jazz. On the surging modal swinger Impressions, meanwhile, Coltrane shows how melodically varied his escapes from the tune’s repeating three-mode chordal loop can be, and how differently he handles tone and line when his mercurial pianist drops out halfway. Improv conundrums but with an unwavering spiritual intent, these on-the-fly Coltrane experiments were part of a 1960s step-change in the evolution of jazz and much else in contemporary music, still making waves from those long-gone analogue days to the eclectic present.

GORILLAZ, Now Now (CD/LP)

During almost two decades in business, the mightiness of Gorillaz has been its mutability – it’s a pop-rock-hip-hop-free-trade- zone where anyone from Lou Reed to Vince Staples could show up and work a groove. But that’s also been its flaw: While last year’s Humanz brought some fire (notably the Pusha T- Mavis Staples collab “Let Me Out”), it felt more like a streaming algorithm than a coherent album. Mastermind Damon Albarn solves this particular problem on The Now Now, the sixth Gorillaz set since he launched the project, an integrated polyglot pop LP about, fittingly enough, the need for unity in fragmented times. Formally, it echoes the 2010 fan club giveaway The Fall: radically shortened guest list, written-on-the-road simplicity, songs named for locales (in this case red, blue and otherwise — “Kansas,” “Idaho,” “Magic City,” etc.) The songs are better, though, and they don’t waste too much time on regionalism. “I don’t want this isolation/See the state I’m in now?” Albarn sings on “Humility,” opening with a vintage chilled-out summer jam certified with sugary licks by soul jazz touchstone George Benson. “Lake Zurich” is gleaming ‘80s synth-funk with a spoken word ramble involving a tunnel between Europe and the U.S. “Hollywood,” the sole tag-team showcase, is a buoyant Funkadelic-styled tribute to Tinseltown in all its parti-colored falsity, with house-music vet Jamie Principle commanding “freaky people, clap your hands!,” Snoop Dogg delivering old-school boasts in updated flows, and Albarn playing the baked tourist. While The Now Now works as a piece, it does lack the sparks that come from the usual Gorillaz mess of ideas and personalities—the upside and downside of all bands, of course, as with most functional democracies. On “One Percent,” Albarn conjures a race of people searching and listening to one another “on the training ground for the new world.” It’s optimistic by his usual gloomy standards, especially compared to the apocalyptic vibe of Humanz. But it’s on point, and a pretty good metaphor for our present now now.

JIM JAMES, Uniform Distortion (CD/LP)

Jim James is certainly prolific. There have been seven albums of resplendent melodies while fronting My Morning Jacket, his solo albums have careered from acoustic balladry and spacey disco to ghostly 1920s-style crooning, and he also joined Conor Oberst in Monsters of Folk. Throughout, he has not lost his trademark musical wonderment and transcendent, childlike nostalgia. However, here he tears up the plans and turns up the guitars for an unexpectedly playful album which rollicks between big-chorused bubblegum pop and crunching hard riffola. The hard-boogieing You Get to Rome echoes, implausibly, Status Quo’s Rockin’ All Over the World. There are Crazy Horses-style frazzled jams, audible guffaws and even, for heaven’s sakes, a yelled: “Let’s rock!” Yet lurking within the seemingly carefree racket lies a giddily powerful response to these troubled times. Throwback’s wistful theme – “When we were young … All the potential in the world” – is cast against fears of the future. It’s one of his finest songs. The lovely, Fleetwood Mac-type ballad Secrets carries similar foreboding. Better Late Than Never and Over and Over are melodious songs in which empires fall but people “drop the same bombs, build the same walls”. Even the syrupy Too Good to Be True is laden with little barbs (“I never once believed that things could go so wrong / I guess I’ll leave it in a song”). His mix of musical joie de vivre and lyrical home truths prove fiendishly effective.

RAY DAVIES, Our Country: Americana Act 2 (CD/LP)

Like his 2017 release Americana, Davies’ new album is a collection of songs and spoken-word bits about living and working in the United States, and the hold this country and its mythology have had on him since he was a kid: Hollywood glamour, the untamed west, the sense of impregnable security and endless possibility. With guitarist Bill Shanley and alt-country group the Jayhawks reprising their role as his backing band, as well as some help from a horn section, a choir and a selection of other musicians, Davies dabbles in a pre-rock rhythm & blues sound in the trebly guitar riff and swinging beat on “Back in the Day,” rootsy New Orleans swing “A Street Called Hope” and country-folk in the steel guitar and mandolin on “Bringing Up Baby.” They’re among 16 new songs and a few re-imagined tunes from his extensive catalog with the Kinks and as a solo artist. Davies pays particular attention to New Orleans here, and not just in the musical arrangements. “It seems that all the music that inspired me started here, then drifted up the big river to become rock ’n’ roll,” he says in a spoken-word bit through layers of wordless vocal harmonies and acoustic guitars on “Calling Home.” New Orleans is also where Davies was shot in the leg in 2004 while chasing a mugger. It’s no surprise then that his fascination with America is tinged with wry, can’t-look-away aversion: he describes a sense of well-being as dawn breaks on “Louisiana Sky,” but confesses to feeling creeped out “with all the talk of voodoo / The living dead / And the zombies everywhere” on “March of the Zombies,” a slinky number stacked with horns. Our Country: Americana II isn’t explicitly a political album, but there are political overtones these days to any album whose subject is America, particularly one that opens with a song called “Our Country.” That’s a loaded term lately, when the historical promise of a melting pot is at odds with the current reality. “Different cultures, race and creed / Building a society / Gone is the land I used to know so well,” he sings on the song, which plays like an updated “This Land Is Your Land,” with choir-like backing vocals. Turns out Davies is singing about his native England, but you couldn’t tell for a minute, could you? In the end, despite his fondness for America, Davies embraces his origins and heads home. “I am a Londoner, after all,” he says on “Epilogue,” before ripping into the rollicking album closer “Muswell Kills,” which recreates his mugging and includes a payback fantasy. Despite a career stretching back decades, Davies will probably always be best known for the scabrous guitar riffs powering the early Kinks singles “You Really Got Me” and “All Day and All of the Night. Yet this more rustic sound suits him. Our Country: Americana II and its predecessor, along with Davies’ 2013 memoir Americana, offer an outsider’s perspective on the beauty and peril of America, a land of confounding contradictions. Davies doesn’t judge, he simply tries to understand. Maybe seeing ourselves through his eyes will have a similar effect on us.

BULLET FOR MY VALENTINE, Gravity (CD/LP)

LATE BLOOMER, Waiting (CD/LP)

MILK CARTON KIDS, All the Things That I Did and All the Things That I Didn’t Do (CD/LP)

KILLER REISSUES:

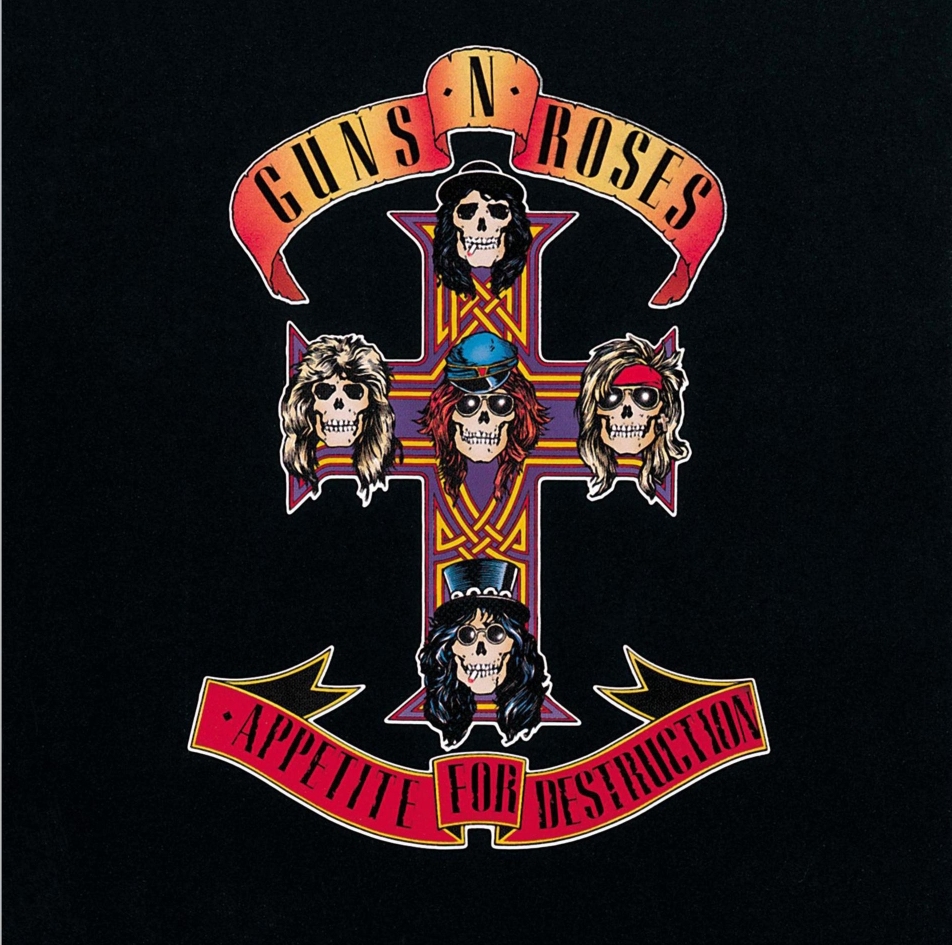

GUNS N’ ROSES, Appetite For Destruction (2xCD/2xLP/4xCD + Blu Ray)

When Guns N’ Roses exploded from the Sunset Strip with lyrics like, “West Coast struttin’, one bad mutha, got a rattlesnake suitcase under my arm,” they were a vision of piss n’ vinegar at a time when Steve Winwood was topping the charts. Apart from Axl Rose’s mile-high coiffure, Appetite for Destruction was the opposite of everything going on in the mainstream: it sounded raw, nasty and dangerous. They were a fully formed statement, capped off with an exclamation point. And a little over a year after it came out, “Sweet Child O’ Mine” would be the Number One song in the U.S. A new, multi-disc box set, which comes either as a $179 super deluxe edition or a for-fans-only, $999 “Locked N’ Loaded” mega box, provides a new, nearly comprehensive look at the group Rolling Stone declared “the world’s most exciting hard-rock band” right out of the gate in 1988. In addition to the original album – which is remastered here and remains a document of rock & roll perfection – the collection contains EP tracks, B Sides, rarities and a heap of previously unreleased demo recordings that chronicle Appetite for Destruction’s evolution. The first bonus disc sports material that should be familiar to casual fans, since more than half of it comes off the Lies EP, home to the whistle-ballad “Patience.” The only song they’ve omitted is the cringe-worthy hate rocker “One in a Million,” which smears African-Americans, Middle Easterners and homosexuals over the course of six minutes; you could say they’ve grown up, though it’s still readily available to stream on Lies. The rest of the volume contains live versions of the ripping “It’s So Easy” B Side “Shadow of Your Love” (a tune that really should have made it onto Appetite) and covers of AC/DC’s “Whole Lotta Rosie” and Bob Dylan’s “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door.” The Dylan cover is impressive because it shows how the quintet had worked out the song’s arrangement years before they recorded it for Use Your Illusion II. The rest of the set contains selections from the band’s 1986 demo session at Sound City Studios with former Nazareth guitarist Manny Charlton producing, along with other outtakes. Although it doesn’t contain the complete Sound City session – Charlton asked them to record every song they were playing live at the time, amounting to nearly 30 tracks including some double takes – the tunes included here are enough to show where the group’s headspace at the time. Rose was parsing which words to emphasize in “Welcome to the Jungle” (“You’re a very sexy girl”). Slash was finding his smooth, bluesy tone on an early version of “Back Off Bitch” (later recorded for Use Your Illusion I). And the band was generally having fun in ways that could never have foreshadowed the acrimony that surrounded its Chinese Democracy era, as Rose name-checks Slash and Izzy Stradlin in “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” and they all sing a goofy intro to an acoustic version of “Move to the City” in unison. It also shows the band at it most naked. For as raw as Appetite sounds, the group was even rougher early on. There’s no synthesizer, coach whistle or extra false endings on the Sound City version of “Paradise City”; it’s simply a pure guitar rocker. “Rocket Queen” originally had a janky transition into its girl-group–inspired coda (“whoa-oa-oa-oa”) before Stradlin and Slash worked out the monolithic, heavy-metal riffs that fans fist-bang to at concerts these days. And even though Rose had been toying around with “November Rain” since before Guns N’ Roses formed, the two versions here (one with a piano accompaniment and another with acoustic guitar) show the crude emotion he was channeling for the tune years before the band recorded it. The most revealing songs here are the ones that didn’t make the cut on any GN’R release: an instrumental take of the rocker “Ain’t Goin’ Down,” which has a groove like “Anything Goes”; a one-minute blues ditty called “The Plague” that’s equal parts Stephen Sondheim and Alice Cooper; and “New Work Tune,” a joyous, instrumental acoustic jam that ends with one of the guys saying, “Yeah, we should work on that.” They never did finish it, and with the 10th anniversary of their last album, Chinese Democracy, approaching, you can’t help but wonder what else they have in the vaults. The rest of the box set contains a Blu-ray with a 5.1 surround mix of the original album, a few bonus tracks and music videos for the hit singles and a never-completed clip for “It’s So Easy” (which is hard to imagine would ever have made it onto MTV anyway since the song contains bon mots like “Turn around, bitch, I’ve got a use for you” and “Why don’t you just fuck off?”) And there’s a 96-page book of photos from Rose’s archive and memorabilia. The cheaper, super deluxe edition contains a smattering of photos, replica concert tickets and posters, temporary tattoos and a lithograph of the record’s original cover – a Robert Williams painting that depicts the aftermath of a rape (a curious inclusion considering they left off “One in a Million”), while the “Locked N’ Loaded” edition comes in an LP-sized wooden cabinet and contains everything in the super deluxe edition along with vinyl, posters for every song on the album, skull rings, pins and guitar picks, among other items, and, of course, a certificate of authenticity. Do you need any of this? No. But that’s not the point. As with everything Guns N’ Roses from the period, it’s not so much all access as it is all excess. And that’s exactly what you want from a reissue like this. It’ll bring you to your sha-na-na-na-na-na-na-na-na-knees.

DAVID BOWIE, Welcome To The Blackout (Live In London 1978) (2xCD)

This is the CD debut of the Record Store Day release, Welcome To The Blackout (Live London ’78). The album features performances recorded at Earl’s Court in London on 30 June and 1 July, 1978 during Bowie’s “Isolar II” Tour.

COMING SOON:

THE VINES, In Miracle Land (7/6)

COWBOY JUNKIES, All That Reckoning (7/13)

DEAFHEAVEN, Ordinary Corrupt Human Love (7/13)

And don’t forget these STILL-NEW platters that matter!

KAMASI WASHINGTON, Heaven & Earth (2xCD/4xLP)

Ten years ago, British saxophone legend Courtney Pine painted a sobering picture of life as a modern British jazz musician in an interview with the Guardian. For all the study involved in becoming one, most jazz musicians had no hope of making a living, unless they were one of the clean-cut vocalists content to ring-a-ding-ding their way through the great American songbook to the delight of Michael Parkinson: you could fully expect your weekends to be spent not exploring the outer limits of improvisation, but playing in a wedding band to make ends meet. “An incredible sale in this day and age is 3,000 copies,” he lamented. Here was evidence of how modern jazz lurks on the very fringes of mainstream public consciousness. You could fill a book with ways jazz has influenced rock and pop – from post-punk’s skronk to the samples of hip-hop and trip-hop – but apart from the aforementioned ring-a-ding-dingers, no serious jazz musician has really crossed over to huge mainstream success since the 1970s, the era of Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew and the Mahavishnu Orchestra, of the super-smooth George Benson and Grover Washington Jr, and of Keith Jarrett’s Köln Concert wafting around in the background of dinner parties. All of which makes Kamasi Washington faintly extraordinary. His last London gig was not at the intimate Servant Jazz Quarters, but the Roundhouse, a venue at which the audience was clearly not comprised of longstanding jazz buffs. He records for Young Turks – home of the xx, FKA twigs and Sampha – and is reviewed in the kind of places jazz artists seldom get a mention. It all seems to have been achieved without pragmatic compromise. The record that catapulted him from self-releasing CDs in amateurish home-made sleeves, 2015’s The Epic, was a three-hour-long concept album. Various theories exist as to how Washington has pulled this off, all of which are supported by The Epic’s full-length follow-up, Heaven and Earth (by Washington’s standards, this is a work of economy, clocking in at a mere two-and-a-half hours). One is that the time is simply right: his guest appearances on Kendrick Lamar’s epochal To Pimp a Butterfly didn’t merely elevate his profile, they established him as “the jazz voice of Black Lives Matter”, in a grand tradition of jazz as black protest. Heaven and Earth frequently appears to be a furious state-of-America address. You can hear portentous anger in everything from its track titles – Street Fighter Mas, Song for the Fallen – to its astonishing opening cover of the theme from 1972 kung fu movie Fists of Fury, which arrives not merely extended to 10 minutes, but with additional lyrics: “Our time as victims is over / We will no longer ask for justice.” Washington’s sound tends to the maximalist – he is not a man afraid of breaking out the orchestra and choir – but on the album’s closing tracks Show Us the Way and Will You Sing it doesn’t feel dense so much as tumultuous, the former heaving and yawing behind a high-drama choral arrangement, the latter calmer, but with its ostensibly positive message of empowerment and change underscored by noticeable darkness. It sounds more like storm clouds gathering than sunlight breaking through. Another theory is that his sound is audibly rooted in the kind of old jazz texts that non-jazz buffs tend to recognise, the kind of thing that gets collected on hipster-friendly compilations released by Soul Jazz and Strut: the spiritual jazz of John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders, Sun Ra’s big band Afrofuturism, the political funk of Archie Shepp’s Attica Blues, the synth experiments of Herbie Hancock and Joe Zawinul. They’re all present here, further smoothed with ample references to early 70s soul and funk, not least the ambitious, orchestrated psychedelia of Rotary Connection. But what’s striking about Heaven and Earth is how expansive and ever-changing it is, its musical focus shifting constantly from lavish grandiosity to perspiration-soaked Latin rhythms to concentrated improvisation, from the edge of chaos to the lushly melodic – sometimes within the same track, as on The Invincible Youth. It never lingers in one place long enough for its running time to seem gruelling. Instead, Heaven and Earth feels writhingly alive and passionate, angrily of the moment but inclusive. If describing Heaven and Earth as “jazz for people who don’t like jazz” sounds pejorative, it isn’t meant to be. Rather, it’s simply to indicate that on Heaven and Earth, Washington continues to explore a sweet spot between artistry and approachability. Whether his success will lead audiences to further explore music that usually exists on the fringes is an interesting question. What is more certain is the quality and accessibility of his own music.

DAWES, Passwords (CD/LP)

California band Dawes dip their observant takes on our days of angst deep into a tub of ‘70s folk and soft rock, turning “Passwords,” their sixth album, into a soothing, sugar-coated collection with a bittersweet lyrical aftertaste. Led by singer-guitarist-songwriter Taylor Goldsmith, the 30-somethings in Dawes must know the catalog of authoritative artists of the era like The Eagles, Jackson Browne and Stephen Bishop to a tee, though they often add a twist or two of their own. The power chords of opener “Living In the Future” and a scarily intense guitar solo are a good match for the lyrics, which read like a directory of modern challenges, from keeping your passwords safe and remembering them to feelings of living on the edge and anticipating being pushed off. “Feed the Fire” offers electric sitar and a melody like Stevie Nicks fronting Hall & Oates, while “Crack the Case” wishes for a lasting armistice — “It’s really hard to hate anyone/When you know what they’ve lived through.” “I Can’t Love” buries the lead (”you any more … than I do right now”) and “Mistakes We Should Have Made” is an energetic burst into regret with vocal assistance from Jess Wolfe and Holly Laessig from indie pop band Lucius. There’s some late ‘80s Joni Mitchell in “Time Flies Either Way,” which ends the album with affecting piano playing from Lee Pardini and acts as a possible sequel to “Telescope,” about a boy whose life never seemingly recovers from his dad’s departure. Or maybe it still can. Dawes achieve a uniform veneer on “Passwords,” translucent coats of sound spread over situations and stories well worth listening to.

T. HARDY MORRIS, Dude The Obscure (CD/LP)

Considering the weight of the ideas T. Hardy Morris is exploring on his new record Dude, The Obscure, it feels like his airiest work yet. Following 2015’s twangy Drownin’ On a Mountaintop, Morris is shedding some skin and getting at something a little rawer and more heartfelt. Dude, The Obscure soars and floats, at once dreamy and heady, even when Morris is rocking out (as he is prone to do). Questioning his place in the world, and striving to stay present in an ever more chaotic world, Morris digs deep on this album and seems to have found his own bliss in the process. A cheeky play on famed English author Thomas Hardy’s novel Jude The Obscure, Dude, The Obscure sounds like a stoner’s spaced out tagline. And in many ways, the album gives us that vibe of getting so deep in your head to where it’s murky and dark, until you ultimately come out the other end feeling more like yourself. On “The Night Everything Changed,” Morris gets nostalgic for good times on the road and feeling connected to others by the memories we share. Recounting faraway cities, missed planes, and wasted money, Morris weaves a sweet, sublime thread made even more magical with the glide of steel guitar. “When the Record Skips” is a dark, heart-thumping ode to the idea of a legacy and what gets left behind. And though “Be” opens the record, it feels most like a culmination for Morris. It’s the album’s stunning peak, and a moment of reckoning as Morris strips away all the clutter that keeps him from moving forward. Hailing from the artsy Southern enclave of Athens, Georgia, Morris hasn’t lost his twang, but this time around, his sound is elevated and meditative. He creates a big sound on Dude, The Obscure, with swooning arrangements that live somewhere above us and that compel us to look upward and reach for them to try and catch just a little bit of that sweet enlightenment within them

NINE INCH NAILS, Bad Witch (CD/LP)

Mutation as a theme has always rippled through Trent Reznor’s songwriting, and his most recent work finds him shifting emphasis from personal to social forms of transformation and decay. The Nine Inch Nails frontman may have once fixated on frenzied individual self-destruction, but with the band’s ninth album, Bad Witch—a six-track, 30-minute release that’s technically part of a recent trilogy of EPs—he wrestles with his dismay over being part of a depraved culture that’s showing signs of impending collapse. While 2016’s Not the Actual Events explores dissociative identities and 2017’s Add Violence brims with paranoia about our increasingly simulated reality, Bad Witch moves past such insular anxieties and more directly acknowledges that society’s chaos is the result of our collective hubris. Amid a kinetic drum loop and flurries of discordant electronic effects, “Ahead of Ourselves” asserts that civilization has devolved into a “celebration of ignorance.” Reznor blames the exponential advancement of technology for magnifying humanity’s basest impulses. The music mirrors an unwieldy, world-gone-mad atmosphere, as a chugging beat lurches in fits and starts and Reznor’s vocals oscillate from frayed, modulated warbles to salvos of abrasive distortion. Elsewhere, on the fuzzed-out “Shit Mirror,” Reznor internalizes America’s “new face,” one that he can barely recognize and that feeds on “loathing, hate, and fear,” his vocals fluctuating from nearly indecipherable, distortion-laden bursts to breathy whispers. He considers this contorted reflection with a shrug, resigned that the mutation staring back at him “feels all right.” Bad Witch‘s emphasis on disorientation and dissonance is most pronounced on “God Break Down the Door,” as a cyclone of swirling electronic loops, syncopated drums, and saxophone is juxtaposed by a calm, sonorous croon heavily indebted to David Bowie. Reznor belabors that vocal approach on “Over and Out,” a moody, sub-bass-driven track in which he retreats into well-worn sentiments about repeating the same mistakes as time flies by. Reznor conveys a bleaker and more visceral sense of desperation on the album’s two instrumental tracks. The shape-shifting textures and cacophonous horns of “Play the Goddamned Part” echo the unsettling disorder of our modern discourse, while the Lynchian otherworldliness of the haunting and cinematic “I’m Not from This World” thrums with an ineffable—yet relatable—sense of unease that drives home Bad Witch‘s exploration of confronting a once familiar environment rendered alien and grotesque.