JOSHUA REDMAN, Still Dreaming (CD)

There’s a tension in Joshua Redman’s new album, Still Dreaming, and it may not be the one that you expect. For the last couple of years, Redman, a saxophonist within jazz’s first tier of prominence, has led an agile post-bop group with Ron Miles on cornet, Scott Colley on bass and Brian Blade on drums. He formed this quartet to pay homage to Old and New Dreams, a band active from the mid-1970s to the mid-’80s, with his father, Dewey Redman, on tenor saxophone. For this among other reasons, Still Dreaming was always bound to be understood in terms of a lineage. Old and New Dreams was first and foremost a proud continuation of the elastic, ecstatic and volatile group cohesion forged by Ornette Coleman in the 1960s and early ’70s. In addition to Dewey Redman, the band featured cornetist Don Cherry, drummer Ed Blackwell and bassist Charlie Haden. As alumni of Coleman’s distinctive sound world, these artists were torchbearers — with the implicit proviso that bearing a torch is all about illuminating the unknown. Joshua Redman is a different sort of musical explorer. As an improviser and a bandleader, he tends to strike an elegant balance between logic and risk. He isn’t a headlong, impetuous type, nor someone who favors a frayed edge. When he first invoked his father, obliquely, early in his career — on the 1993 album Wish, which reunited most of the lineup from Pat Metheny’s Rejoicing — it was more an acknowledgment of birthright than a pledge of allegiance. Still Dreaming goes a lot further to stake a claim, with evident sincerity and total commitment. As Redman would be happy to point out, he isn’t the only one here with a connection to his predecessor. Colley is a direct protégé of Haden, and Miles is a longtime admirer of Cherry. Blade hails from Louisiana, as Blackwell did, and brings a similar bounce to his groove. From the album’s opening track, a Colley composition called “New Year,” you hear the soulful crosstalk and jostling cadence of Old and New Dreams’ style — and by extension, Coleman’s. The rhythmic undertow in this band feels true to its inspiration, as does the airtight-yet-relaxed rapport between Redman and Miles. (Hear how they phrase the stutter-stepping melody on Redman’s aptly titled “Unanimity.”) All but two of the tracks on the album, which clocks in at a tight 40 minutes, are new pieces by members of the band. And those two exceptions are persuasive. “Playing,” a coltish theme by Haden, yields vibrant results — not quite as wild and thrashing as the original studio version, but still full of urgency and spirit. It flows right into Coleman’s “Comme Il Faut,” from the 1969 album Crisis, which Redman’s crew interprets with the solemn concentration of a liturgy. There’s more equipoise and eloquence here, in conventional terms, than there was in Old and New Dreams. But because each musician brings so much earnest conviction to the table, that feels right and just; the music wouldn’t ring truthful otherwise. And it’s not overstating the case to say that this framework stretches the musicians in salutary ways. When Redman begins his tenor solo a few minutes into “Blues For Charlie,” his blurry vocality actually evokes Joe Lovano (a lifelong Dewey fan), without tipping into ventriloquism. On “Haze and Aspirations,” a gorgeous Colley waltz, the tenor solo is a marvel of emotional resonance and thematic coherence — a world of expression, compressed into a minute’s time.

KASEY CHAMBERS, Campfire (CD)

Kasey Chambers has never denied her Australian country roots and here the link is further defined by the language and personal experiences from her and her contributors. US country (via Emmylou Harris) is also strongly displayed on The Harvest & The Seed, and there’s a nod to the Chambers legacy itself with This Little Chicken feat Bill Chambers (listed simply as “My Dad” on the sleeve). In less accomplished hands the themes and sounds – classic banjo, harp and gospel – would be in real danger of sounding stale, but Chambers leads with strength and mastery. Highlights include the direct Abraham, the soaring harmony of Early Grave, the call and response of Big Fish, the grunt of Now That You’ve Gone and infectious The Campfire Song. Little moments of chatter like the intro to Junkyard Man also prove that making this music seems to be as joyful an experience as it is to hear. A great Australian storyteller and collaborator – Chambers is a deadset legend who continues to just get better.

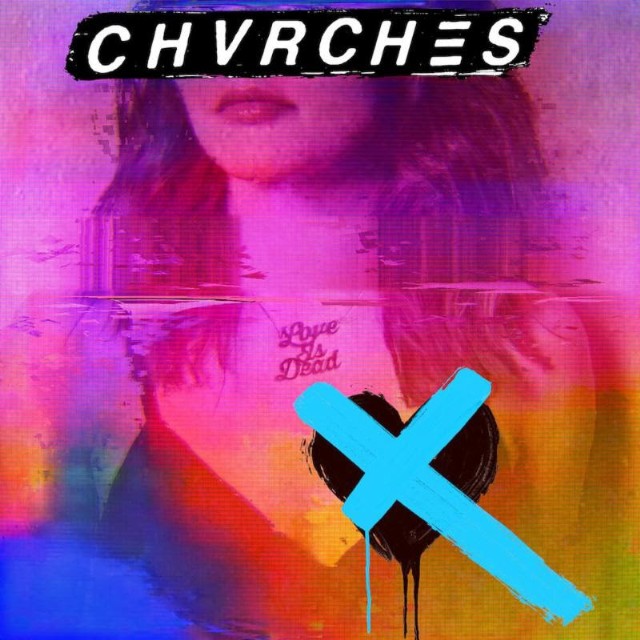

CHVRCHES, Love Is Dead (CD/LP)

Since forming in 2011, the Scottish trio Chvrches have refined synth-pop for the festival age, taking the chilly atmospherics of early electro and piling on flourishes designed to divert distracted attendees’ attentions away from art installations and friends’ conversations, with vocalist Lauren Mayberry’s airy soprano contorting into stretched-out pleas and percussive stuttering. It’s partly cloudy music, defined by the way its dreariness balances with the glimmers of light that shine through. For their third album, Chvrches have enlisted Greg Kurstin, whose studio skills have turned Tegan and Sara’s sharply angled harmonies into a baseline for pop euphoria and given Beck a solid middle ground between his genre-bending experimentalism and his singer-songwriter side. Kurstin’s signature doesn’t lie as much in his sonics as it does in his ability to coax out maximalism from the artists he works with, and on Love Is Dead Chvrches appropriately level up, even on the tracks where he isn’t credited. “Deliverance” is spiky yet inviting, its lyrics poking at the hypocrisy of religion; “Never Say Die” builds its drama with swooning synths, with Mayberry’s clipped “never-never-never” on the chorus providing an italicized exclamation point. These songs, like the album’s other highlights, show how Chvrches are at their finest when they’re adding dabs of holographic highlighter to structures built on New Wave’s buzzy bliss and post-goth’s gloom.

GRAVEYARD, Peace (CD)

Sweden’s crown princes of swinging retro cool announced their split in September 2016, one year after releasing their quirky, soul-infused fourth album, Innocence & Decadence. The news came as quite a surprise, as this hotly touted quartet’s sole raison d’être always seemed to be a simple, overriding passion for playing honest, righteous, gut-level rock’n’roll. They were still bringing new twists and influences to bear on their sound, while their fanbase was continuing to grow thanks to many high-profile support slots, festivals and headline tours. Only a scanty handful of naive souls could have imagined that Graveyard were seriously gone for good, but even fewer imagined that this dissolution would barely last four months – not so much a hiatus, more a mini-break, the band coming across as a little bit histrionic and indecisive. Whatever their reasons – the drummer’s changed, if anyone was likely to notice – it’s lent an additional sense of urgency and jubilation to this comeback LP’s aptly titled shit-kicking opener, It Ain’t Over Yet, instantly impressing with an improved production that emphasises directness, looseness, warmth and humanity. And although the heavier numbers like Cold Love, Please Don’t and Walk On have a strutting-cock swagger that’s plugged straight into the rarefied magic of early 70s hard rock heroism, Graveyard are equally adept at the moments of hushed vulnerability. The mellow atmospheres of more sensitive cuts like the Jeff Buckley-ish See The Day, the brooding, nocturnal Del Manic, The Fox’s earthy flirtation with Nirvana’s About A Girl and the emotive singer-songwriter shades of Bird Of Paradise are so finely wrought you can’t help hoping that one day Graveyard apply themselves to delivering their Led Zep III – although, hopefully, not after any more premature, fleeting disbandments.

SNOW PATROL, Wildness (CD/LP)

Snow Patrol, once such a mainstay of the UK music scene, has been notably missing in recent years, with writer’s block cited as the main cause for the absence. In 2012, Gary Lightbody told NME that the band had scrapped an album’s worth of music which had been replaced by ‘mind-boggling’ material, but the extension of time between the band’s last full length LP in 2011, and the upcoming release of Wildness, is likely to make the band’s long-term following approach the record with trepidation. The band’s seventh studio album is a strong improvement on its predecessor, Fallen Empires, and opens with the fantastic ‘Life On Earth’. The opener begins quietly and builds to a triumphant resolution. The band’s signature singalong potential is there; the rousing lyrics coupled with simple instrumentation are definitely a winning formula here. The lead single from the album, ‘Don’t Give In’, follows on. This track is one which appeals to me less from the album; Lightbody’s vocal style is a little raspy and it’s lyrically clunky. ‘Heal Me’ is a good song, but perhaps not a highlight of the record, and ‘Empress’ is more upbeat. ‘What If This Is All The Love You Ever Get?’ is another stand-out point, and sounds a little like ‘You Could Be Happy’ pt. II. The balance between emotion and sentimentality is struck really well here; the song tugs at the heartstrings but without being too overwhelming or insincere. Lyrics like: “What if it hurts like hell? Then it’ll hurt like hell/ I’m in the ruins too, I know the wreckage so well” are just some of Lightbody’s lyrical pearls which embellish this particular track. ‘Youth Written In Fire’ details the spark in a relationship fading, but does it poetically and imaginatively. The harmonies in this song are stunning. ‘Soon’ is a little off the beaten track, and sounds more like a solo track about paternal relationships. It brings variety to the album in its own way. The fiery passion of the first track makes a comeback in ‘Wild Horses’, with the same charging, powerful melodies which have made ‘Eyes Open’ and other albums so emotionally in tune. The closing track, ‘Life and Death’, is contrastingly calm and melodically intricate, scattered with delicate harmonies. It builds to a more intense ending. Overall, Wildness is a really great comeback record.

THUNDERPUSSY, Thunderpussy (CD/LP)

THE SMITHEREENS, Covers (CD)

JONATHAN DAVIS, Black Labyrinth (CD)

DAVID WILCOX, View From The Edge (CD)

KILLER REISSUES:

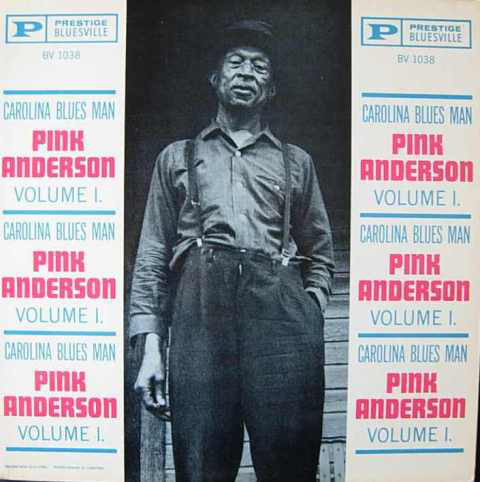

PINK ANDERSON, Carolina Blues Man/Medicine Show Man (CD)

A vast majority of the known professional recordings of Piedmont blues legend Pink Anderson were documented during 1961, the notable exception being the platter he split with Rev. Gary Davis — Gospel, Blues and Street Songs — which was documented in the spring of 1950. Carolina Blues Man finds Anderson performing solo — with his own acoustic guitar accompaniment — during a session cut on his home turf of Spartanburg, SC. Much — if not all — of the material Anderson plays has been filtered through and tempered by the unspoken blues edict of taking a familiar (read: traditional) standard and individualizing it enough to make it uniquely one’s own creation. Anderson’s approach is wholly inventive, as is the attention to detail in his vocal inflections, lyrical alterations, and, perhaps more importantly, Anderson’s highly sophisticated implementation of tricky fretwork. His trademark style incorporates a combination of picking and strumming chords interchangeably. “Baby I’m Going Away” — with its walkin’ blues rhythms — contains several notable examples of this technique, as does the introduction to “Every Day of the Week.” The track also includes some of the most novel chord changes and progressions to be incorporated into the generally simple style of the street singer/minstrel tradition from which Pink Anderson participated in during the first half of the 20th Century. Listeners can practically hear Anderson crack a smile as he weaves an arid humor with overtly sexual connotations into his storytelling — especially evident on “Try Some of That” and “Mama Where Did You Stay Last Night.” Aficionados and most all students of the blues will inevitably consider this release an invaluable primer into the oft-overlooked southern East Coast Piedmont blues.

Like volume one of the series of LPs Anderson did for Bluesville, Medicine Show Man was recorded in 1961 (though it was recorded in New York City whereas the others were recorded in Spartanburg, SC). Volume One was mostly traditional songs; these are all traditional songs in the public domain. If you had to split hairs, it seems that Anderson sounds a bit more comfortable in the studio/recording setting on this one than on the others, and a tad less countrified and more urbane. The tone is cheerful and easygoing, like that of a well-loved man entertaining his neighbors. Which is not to say this is a throwaway; the phrasing and rhythms are crisp, and the ragtime-speckled folk/blues guitar accomplished.

GRANT GREEN:

Funk In France: From Paris To Antibes (1969-70) (2xCD)

Slick: Live At Oil Can Harry’s (CD)

There’s a special thrill of liberation in the live recordings of jazz that few studio recordings can match. That thrill is palpable on the two-disk set “Funk in France: From Paris to Antibes (1969-1970),” and “Slick!—Live at Oil Can Harry’s,” and both albums offer revelatory delights. Green recorded copiously from 1961 to 1971, mostly on the Blue Note label, both as a leader and as a sideman, and his musical range was wide. He’s the most original jazz guitarist of his time, along with Wes Montgomery, and Green’s work, whatever the context, maintained an air of abstraction and concentration that was more searching. If Wes Montgomery’s solos are filled with joyous affirmations, Green’s improvisations are filled with question marks that often yield to bursts of insistent fervor. The two new Green releases are different; they offer three performances that are thrilling in themselves, and that also add a major historical dimension to Green’s career, proving that his shift—from what the organist Clarence Palmer, interviewed in the “Funk in France” liner notes, calls “heavy bebop jazz” to “rock and roll”—nonetheless offered both a remarkable continuity and a noteworthy advance in the guitarist’s own art. The first “Funk In France” session, recorded in 1969 with an audience at a Parisian radio studio, is “heavy bebop jazz” with a twist. Green, accompanied by Larry Ridley, on acoustic bass, and Don Lamond, on drums, opens with a propulsively funky number, James Brown’s “I Don’t Want Nobody to Give Me Nothing,” but for the rest of the concert the trio explores the modern-jazz songbook, including two compositions by Sonny Rollins, “Oleo” (which Green had recorded in 1962) and “Sonnymoon for Two” (which he had recorded in 1960). Green’s expansive solos float boldly and fly forcefully above the harmonic intricacies before breaking into starkly rhythmic virtual shouts. Despite his rapid-fire fluidity, Green seems to use his guitar also like a percussion instrument, doing so slyly in his sinuous musical phrases, brazenly at dramatic crescendi. That percussive element comes to the fore in his rock-based recordings of the seventies, but, in these albums, it remains in balance with his long-lined improvisations.

In 1975, at Oil Can Harry’s, in Vancouver, Green—joined by Emmanuel Riggins, playing electric piano; Ronnie Ware, on bass; Greg (Vibrations) Williams, playing drums; and the percussionist Gerald Izzard—starts with a nod to one of his personal classics, Charlie Parker’s “Now’s the Time,” which darts and lurches through the changes with jagged intensity. He revisits Antônio Carlos Jobim’s bossa-nova tune “How Insensitive (Insensatez).” That tune is also part of the 1969 Paris program, where Green’s exhilarating filigreed solo bounces along with the jaunty rhythms; in Vancouver, Green bounces off them, urged onward by Riggins’s assertively florid interjections, with results that are less subtle but far more challenging, replacing a limpid musical stream with a churning musical magma. The thick-textured heat is even more intense in the concert’s final number, a medley of funk and fusion tunes (including the Ohio Players’ “Skin Tight” and the O’Jays’ “For the Love of Money”) that rises to a volcanic eruption that spotlights both the glories and the limits of Green’s style.

COMING SOON:

DAVE ALVIN & JIMMIE DALE GILMORE, Downey To Lubbock (6/1)

BRIAN JONESTOWN MASSACRE, Something Else (6/1)

NEKO CASE, Hell-On (6/1)

And don’t forget these STILL-NEW platters that matter!

COURTNEY BARNETT, Tell Me How You Really Feel (CD/LP)

Back in 2013, Courtney Barnett covered Kanye West’s ‘Black Skinhead’ on Australian radio as a guitar-charged glam-grunge stomp, reframing its outrage in her bedhead Melbourne white-girl flow. It was a questionable yet telling move for a fellow verbose storyteller, delivered just as her single “Avant Gardener” – a deceptively offhand first-person account of an asthma attack – announced the arrival of a rare talent. Now a bona fide indie-rock heroine, Barnett has made a second LP that occasionally recalls her early come-to-Yeezus session. Tell Me How You Really Feel is noisy and way more pissed off than her 2015 debut, Sometimes I Sit and Think, and Sometimes I Just Sit, unsheathing sharp new earnestness alongside her trademark sabers of sarcasm and penetrating observation. She opens by paraphrasing Nelson Mandela. “Y’know what they say/No one’s born to hate/We learn it somewhere along the way,” she whispers at the outset of “Hopefulessness,” a slithering post-punk inspirational that builds from ambivalent incantation to near-snarl, twin guitars cresting into a glorious noise burst before receding comically behind the earthbound wail of a teakettle – a perfectly Barnett-ish touch. Humor, often dark, flickers throughout like a candle. “Nameless, Faceless” – an echo of Nirvana’s “Endless, Nameless” – riffs off a quote from Margaret Atwood, measuring the psychic burden of violence in light of the schism between the sexes. “Men are scared that women will laugh at them,” Barnett intones dryly before the punchline: “Women are scared that men will kill them.” The song is a marvel of tonal control – she expresses sincere-seeming empathy for an Internet troll, laced with acid sarcasm at the notion women must play the role of default comfort dispensers. Similar dual consciousness appears in songs about relationships (“Need a Little Time”) and dream-chasing (“City Looks Pretty”), and in straightforward screeds “I’m Not Your Mother, I’m Not Your Bitch,” a furious punk smackdown that takes a moment for measured self-examination, and “Crippling Self Doubt and a General Lack of Self Confidence,” a passive-aggressive rant egged on by girl-gang backing vocals from the Breeders’ Kim and Kelley Deal, two of Barnett’s foremost indie-rock foremoms. They’re the most Nirvana-esque moments on this modest masterpiece of an album, made by an avowed fan who shows a kindred underdog solidarity. Kicking against the pricks, including the ones in her own head, Barnett encourages us to do the same, with an impressive generosity of spirit. “Take your broken heart/Turn it into art,” she counsels at the LP’s outset. “Your vulnerability is stronger than it seems.” As Tell Me How You Really Feel amply demonstrates, so is hers.

PARQUET COURTS, Wide Awake (CD/LP)

“You should see the wall of ambivalence I’m building!” sang Austin Brown on his band’s 2013 stoned ‘n’ starving slacker-rock breakthrough Light Up Gold. The band sure don’t sound ambivalent now. “Allow me to ponder the role I play/In this pornographic spectacle of black death!” co-leader Andrew Savage hollers on “Violence,” a standout on his band’s fifth LP that conjures both the Fall and Fear Of Music-era Talking Heads, an epic rant about normalized barbarity that spins into a panic attack of tangential nightmares, while a pitch-shifted Vincent Price-sounding-motherfucker cackles menacingly in the background. Indeed, Wide Awake! is the sort of reality-reckoning many of us have been having on a daily basis lately. In place of the usual Parquet Courts concerns – oblique self-analysis, post-graduate existential ennui, meta-rock references, girl problems – are big-picture anxieties and flabbergasted outrage. “Before the Water Gets Too High” questions the pointlessness of craven money-making and earnest protest both in the face of looming climate-change apocalypse. “Total Football” calls out cultural obliviousness (“Have your hurt Caucasian feelings left you so distraught?”) in a post-Kaepernick call-to-action that concludes “Fuck Tom Brady.” Yet they haven’t lost their deadpan wit, offsetting what might come off as shrill or didactic; see “Death Will Bring Change,” which enlists a rag-tag choir of 12-year-olds to drive home the title conceit – in their mouths, a quietly hopeful threat to the powers that be. With light-touch production by Danger Mouse, this is also the funkiest and sweetest Parquet Courts set yet, trading off some of their trademark guitar fireworks for danceable jams. The title track is Eighties Mudd Club boogie-in-the-wreckage punk-funk, complete with cowbells and referee whistles. And the Seventies AM-radio pop strut of “Tenderness” extends a hand to the nihilists, shaking its moneymaker and beckoning them to join the conscious revolution: “You wanna live outside the groove, then fine/But it’s there like a flower, blooming in your ears.”

BRAD MEHLDAU TRIO, Seymour Reads The Constitution (CD)

When Keith Jarrett mixed mainstream pop into a repertory of modernist covers and songbook classics, he established new parameters for piano trio jazz. Brad Mehldau expanded the project by delving deeper into alt rock and pop and sprinkling in compositions of his own. His current trio of bassist Larry Grenadier and Jeff Ballard on drums have been together since 2005 and have long marked the contours of Mehldau’s lines with precision and bite. And, as on this CD, both musicians solo purposefully when required, Grenadier with warmth and a woody attack; Ballard with rattles of snare and rimshots that toy with time. But as good as Ballard and Grenadier are, roles are clearly defined, and there’s no mistaking that Mehldau’s piano is the lead voice. Particularly when, as on this album, the American displays the iron logic that made his recent solo album After Bach such a standout. Mehldau’s compositional rigour is clear from the two originals that open this set. “Spiral” supports a repeated motif with downward-moving harmonies and builds into a drum-feature peak; the title track lives up to its name by unfolding thoughtfully over the gentle slopes of a waltz. Later in the album, Mehldau re-harmonises and toys with the baroque opening line of “Ten Tune” while Ballard is at full stretch; the piece plays out with the pianist unaccompanied, spinning variations with such purpose that they appear pre-composed. Elsewhere, the American’s joyous reading of “Almost Like Being in Love” captures the first flush of a romantic relationship. Bryan Wilson’s “Friends”, taken as a waltz, delivers a serrated landscape of accelerating lines and a brisk and jazzy cover of Paul McCartney’s “Great Day” sits on a bed of counterpoint funk. Mehldau invests all three pieces with ambiguity and depth while retaining the clean lines that made them popular in the first place. The album closes with the lyrical modernism of Sam Rivers’s “Beatrice”, its melody clearly stated so as to linger in the mind.

JOHN WESLEY HARDING, Greatest Other People’s Hits (CD/LP)

First hitting the scene in the late ’80s, Wesley Stace, professionally known then as the singer-songwriter John Wesley Harding, scored some early musical success, especially on the college radio airwaves with songs like “The Person You Are,” “The Devil In Me” and an unlikely cover of Madonna’s “Like A Prayer.” Over 20 albums and collections later, he tends a multi-faceted career as a novelist, singer-songwriter, festival curator, University teacher, and variety show host. Now, he can add singer of greatest other people’s hits to his long list of accomplishments! John Wesley Harding has put together a fantastic compilation of songs by artists as varied as Bruce Springsteen, George Harrison, Roky Erickson, Madonna, Pete Seeger, and Serge Gainsbourg, among others. The collection features Harding’s renditions of songs by these great composers, as well as performances with The Minus Five, Fastball, Eric Bazilian, The Universal Thump, and Bruce Springsteen.

ZIGGY MARLEY, Rebellion Rises (CD)

Rebellion Rises is Ziggy Marley’s seventh studio album as a solo artist. What makes his prolific ongoing output- a new studio release every two years or so- both continually relevant and critically notable is the way in which each latest effort builds on the prior entries in Marley’s illustrious catalog. It’s not that the multiple Grammy-winning singer morphs into a new character, or explores a new genre, so much as it is the unfolding experiences of the introspective journey that the reggae superstar is on; he’s gracious enough, almost reliably compelled, to take us with him. In the case of this record, it’s less vicarious and free as its predecessors. This is one that’s more a call to action: Marley wants you involved. He has tucked, and sometimes shouted, message into most of his writing over three decades as reggae’s most prominent voice, but often it seemed more reporter, less recruiter. Writing, arranging, and producing this album himself, these ten tracks, with a few exceptions, are rallying cries for humanity. Yes, the cause remains love, but this time Marley is calling to unite all the rebels for the cause. The album opens with the set’s most scathing indictment as a djembe rattles and horns shred their way through See Dem Fake Leaders. Marley’s son Gideon delivers a spoken-word bridge on The Storm is Coming, an autobiographical tracing of a phone call Ziggy and brother Stephen shared during hurricane season in Miami that plays as a metaphor for an encroaching political climate. Synth claps and electric guitar lines cycle through World Revolution, that touches on racial discrimination, also marked by a rap on the bridge- this one from an intern, SamuiLL Kalonji, Marley discovered at his record label office. The lighter empathy of Your Pain is Mine follows, with a verse melody reminding of an earlier Marley cut, Beach in Hawaii. Then, the arresting staccato Change Your World, utilizing the timeless boy-meets-girl backdrop as a metaphor for activism. Ska-like horns color the bouncy, bright wish list of I Will Be Glad, as one of Rebellion’s sunnier tracks, both musically and lyrically. High on Life is a bit of a throwback, evoking the innocent charm of Marley’s former group, sibling sensations The Melody Makers, then, fittingly welcoming Stephen for the subsequent Circle of Peace, that affirms the cause and petitions the willing to realize their dreams now. With strumming acoustic guitar and delicate piano runs, I Am a Human works to shed the labels of race, religion, and politics, and return the focus to simple humanity. The titular finale carries something of a core sentiment that has anchored Marley since the beginning. Even in the toughest of times, Ziggy Marley has remained optimistic. The minor-to-major-key shifting within the steady rock of this closer suggests a sense of sunlight emerging from the darkness; that love and peace will win the day. Rebellion Rises is not an angry record. It is not a bitter record. But, it is not a record of hope, either. The time of hoping for change is a notion Marley considers past due. This is a record of action, and for Ziggy Marley, the time for action is now.

STEVE TIBBETTS, Life Of (CD)

One-of-a-kind guitarist and record-maker Steve Tibbetts has an association with ECM dating back to 1981, with his body of work reflecting that of an artist who follows his own winding, questing path. The BBC has described his music as an atmospheric brew… brilliant, individual. Life Of, his ninth album for the label, serves as something of a sequel to his 2010 ECM release, Natural Causes, which JazzTimes called music to get lost in. Like the earlier album, Life Of showcases the richness of his Martin 12-string acoustic guitar, along with his gamelan-like piano and artfully deployed field samples of Balinese gongs; the sonic picture also incorporates the sensitive percussion of long-time musical partner Marc Anderson and the almost subliminal cello drones of Michelle Kinney. Tibbetts, though rooted in the American Midwest, has made multiple expeditions to Southeast Asia, including Bali and Nepal; not only the sounds but the spirits of those places are woven into his musical DNA as much as the expressive inspiration of artists from guitarist Bill Connors to sarangi master Sultan Khan. Life Of has a contemplative shimmer like a reflecting pool, with most of the album’s pieces titled after friends and family, living and past.